- Françoise Hardy : The Yé-Yé Girl From Paris

As well as the German version already mentioned, Hardy recorded Tous Les Garçons Et Les Filles in English (Find Me A Boy) and in Italian (Quelli Della Mia Età). “They had me record Tous Les Garçons... in Italian. Overnight, I was catapulted to number one in the charts. My face was in all the papers. In Italy, it was overwhelming... We travelled in superb convertible cars, people came out onto the streets to see us go by. We found ourselves in stadiums with 50,000 people.” (Paroles et Musique Nouvelle Série no. 9).

The other side of the Alps

In the summer of 1964, Hardy went to Venice with Jean-Marie Périer. Their visit was captured on film by Salut Les Copains magazine.

She returned to Italy in 1966 for the San Remo song festival and for the showing of the film Grand Prix. These visits gave her the chance to record Italian versions of some of her hits. Thus, Et Même became I Sentimenti, for example.

Unfortunately, the results weren’t always convincing. In some cases, it would have been better to keep the original backing tracks and simply cut new vocal tracks. The Italian arrangers had neither the delicateness of the English nor the simplicity of their French counterparts. Perhaps it’s just a question of taste – some critics consider the Italian arrangements to be more elaborate.

This became, effectively, Hardy’s Italian period. It contrasts with her work over the previous two years, during which she had drawn heavily on the Anglo-American repertoire. But she was never as great as when she was writing the music and lyrics herself on gems such as Si C’Est Ça, Comme and Je Serai Là Pour Toi or even on subtler tracks such as Tu Es Un Peu À Moi. Though she was also good when she delegated song-writing control to someone as talented as Guy Bontempelli, such as on Tu Verras.

Sixth album

With this album, the illogical numbering system was finally dropped. The LP was released in November 1966 under the reference Vogue CLD 702- 30. It began extremely well, with Je Changerais D’Avis. This version of a big hit for Italian star Mina, Se Telefonando, came with French lyrics co-written by Jacques Lanzmann, Jacques Dutronc’s frequent accomplice, and music by Ennio Morricone.

Another success was Il Est Des Choses, with music by Edoardo Vianello, the man behind Parlami Di Te, Hardy’s San Remo entry.

1967

In 1967, Hardy created Asparagus, her own production company and promptly signed a new distribution contract with Vogue. The name was inspired by her nickname, the Endive of Twist – L’Endive du Twist. However, her new adventure was soon cut short. After the album En Anglais was released, Hardy became embroiled in a lawsuit.

In the spring, she took part in an avant-garde theatrical piece, Les Vénusiennes. Accompanied by the dancers of the Barbara Pearce ballet, Hardy played the Venusian, representing the emancipated woman of the year 2000 (or 3000). Costumes came courtesy of Paco Rabanne (and Mick Bernard). Guy Pellaert captured them in a comic-like dream world.

Then there was a TV movie – in colour – made by Jean-Claude Lubtchansky in the April. Unfortunately, the show didn’t air until almost a year later, on 4 February 1968. This was disappointing, as it could have been the first French TV broadcast in colour. (That came on 1 October 1967 instead.).

The futuristic nature of the project was nixed by the fact that the four songs that Hardy sang were already well known to the public. In particular, Ma Jeunesse Fout Le Camp had been receiving radio airplay for some time.

Les Vénusiennes should have been performed if not worldwide, then at least across Europe. But it failed, as this article extract from the Belgian newspaper Le Peuple explains: Françoise Hardy saves the day at the 140 after Les Vénusiennes doesn’t take place.

There was a stir at the 140 Theatre on Tuesday night. Ten minutes before the curtain was due to go up, no one knew if the play would happen. It didn’t in the end, and after a half-hour wait, the half- amused, half-angry audience were treated to 40 minutes of Françoise Hardy singing pieces from the show... What happened? The very confused explanations of Monsieur Dekmine, director of the 140, shed little light for the audience and only his very real embarrassment excused the fact that he had not cancelled the show outright. Already by that point, it was clear that Les Vénusiennes couldn’t be presented as hoped. And, given that Guy Pellaert, the writer of this ‘crazy show’ that promised to be more insane than the weirdest of shows, had walked out leaving behind the production, the Ted Lapidus costumes and a distraught theatre director, what happened next was inevitable. It deserved to be cancelled. As she began performing, Françoise Hardy said: “Perhaps you don’t know what’s happened here. Nor do I or the musicians. So let’s act as though nothing did.” The audience, resigned after such a long wait, were keen to play along and Françoise Hardy’s set was received warmly. She deserved it, if only for daring to confront an audience in a bad mood. Also, the choice of songs was pleasant because she has a very modern style on stage, because her musicians and her three young backing singers accompanied her intelligently if sometimes a little noisily.

Et voilà...

Among the successes of the year, Voilà (EP EPL 8566) was a particular delight – but one that almost failed to see the light in France. “I had written it solely to record in Italian, then, afterwards, we thought it would be funny to cut it in French too. A friend I like a lot said to me, ‘It’s madness to do it in French, it’s old-fashioned, you’re wrong.’ I was really shaken because I thought, after recording it that it was the strongest song on the record...” (Le Désespoir De Singes... Et Autres Bagatelles).

Hardy wasn’t mistaken. It was this song that took off, reaching number five in the charts in June that year. On the same EP could be found the gem Au Fond Du Rêve Doré. This song was so good that you could be forgiven for thinking that John Lennon might have taken inspiration from it for Jealous Guy. For this release, the British orchestra was gone – instead, that of Jacques Denjean was on three tracks, and that of Jacques Dutronc on the fourth.

The yé-yé girl from Paris was everywhere, in a whirlwind of activity. Via her record company, she sent a postcard from Brazil to her fans. In the summer of 1967, for TV broadcasts, she holidayed in Germany’s Saarbrucken and Frankfurt. Then – according to Salut Les Copains magazine, at any rate – she was in Portugal to open for Frank Sinatra for President Salazar, before partying in the UK, in Cambridge. Then came Spain and Italy.

Finally, back in France, she undertook a tour of casinos before returning to Paris to prepare for recording sessions.

In February 1968, she toured UK universities, taking in Brighton, Cambridge, Durham, Birmingham and Southampton. After a year or two more of this sort of hectic schedule, she would decide to quit appearing live.

In the meantime, she had to keep her booked appearances, including a

three-week tour of South Africa in early 1968. There, Now You Want To

Be Loved, an English-language take on Ronds Dans L’Eau was at

number 13 in the charts. “In those days, gigs lasted a maximum of 45

minutes, the songs were short. It was much easier. Nowadays, you have

to be on stage for two hours and people expect a fully-fledged show. I

couldn’t physically do it, I’m not strong enough. In addition, I need

markers to be able to sing. When musicians play the intro, I have to work

out in my head in what tempo and at what moment I need to start

singing.” (Record Collector, interview, 2005).

This recurring problem had already been evident during her first auditions

back in 1961: “It was noticed that Françoise had serious difficulties with

the meter. ‘I suffer less from it today,’ she says, ‘but I still have to

measure out the tempo with my hand so that I don’t lose myself.” (Salut

Les Copains, no. 31, February 1965) “Sometimes people reproached her

for her stillness on stage, her refusal to gesture. For me, not only have I

got used to this fixedness, but I think Françoise could push this even

further. Even frozen like a statue, she would be still be admirable. (Lucien

Morisse, Director of Programmes, Europe no. 1, Salut les Copains no.

31, February 1965).

The international queen of cool

A true fashion icon, Hardy was called on to represent Courrèges globally, wear a dinner suit by Yves Saint-Laurent, don a suit of gold armour by Paco Rabanne... (The latter was a unique piece designed especially for her, worth a cool 12 million francs at the time.).

Rabanne created an event where the singer could wear “the world’s most expensive mini-dress”, made of golden squares encrusted with diamonds: the opening of the International Diamond Exhibition.

Unfortunately, the date of the opening fell on 15 May 1968, just as riots were starting in Paris.

Hardy’s record company insisted that she stay away from the capital. So she found herself in Corsica instead. Like her, other big stars such as Johnny Hallyday – another mouthpiece of French youth – were encouraged to keep out of Paris.

May 1968... and then what?

After May 1968, everything changed. Sheila and Richard Anthony sold fewer records. Adamo remained out of sight. Brigitte Bardot took a lower profile and France Gall disappeared from the charts. Dick Rivers too.

Christophe and Hervé Vilard packed their bags and became more popular in South America than at home. Antoine continued to disappoint.

Eddy Mitchell clung on by his fingernails...

Fortunately, not all the decade’s stars were in the same boat. Hardy, for example, kept going strong. Because she never ranked as the top star of the day, she couldn’t be accused of being in decline. She continued to release records and they sold just as well as those of her competition – and for longer. Des Ronds Dans L’Eau, issued in 1967, remained in the charts well into 1968, without being affected by Nicole Croisille’s success with the title track of Claude Lelouch’s film Vivre Pour Vivre (known as Live for Life, in English).

What’s more, Comment Te Dire Adieu, wasn’t as its lyrics would suggest: “disposable like a Kleenex”. It made number three in March 1969 and is considered something of a classic today.

All her work of the period sold well – both her LPs and her singles.

Ma Jeunesse Fout Le Camp

Up until this point, Hardy’s albums had been issued with the regularity of a metronome: every year, in November. This album would be the exception to the rule. Quite whether there was any significance in this is open to debate.

Whatever the case, an impressive list of writers had been lined up for the album. Aragon and Brassens for Il N’Y A Pas D’Amour Heureux, Pierre Barouh and Raymond Le Sénéchal for Des Ronds Dans L’Eau, Guy Bontempelli for Ma Jeunesse Fout Le Camp, Danyel Gérard and Daniel Ortis for the superbly delicate Elle Est Trop Loin (for which Hardy feminised the lyric), and Jean-Max Rivière and Gérard Bourgeois for La Fin De L’Été.

With the sole exception of Mon Amour Adieu, a cover of 1964’s Baby Goodbye by Kenny Rankin, the album was a true French original.

The new decade

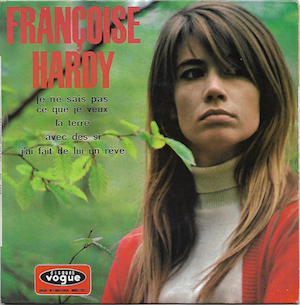

At the very start of the 1970s, Hardy experienced a dip in her fortunes. It had begun in the wake of May 1968, when her EP Je Ne Sais Pas Ce Que Je Veux proved one of her least popular. There was no good reason for this. The lead track was a superb cover of Tiny Goddess by Britain’s Nirvana (no link to the Kurt Cobain group). The other three songs, J’Ai Fait De Lui Un Rêve, La Terre and Avec Des Si, were all her own compositions and each was excellent.

One fan wrote the following on YouTube about Avec Des Si: “One of Françoise’s most beautiful songs (words and music!). Why was Françoise so modest about the songs she wrote? The soaring vocals underline the ‘Si’, preventing the song from being cutesy; a simple and effective guitar. Great orchestration!”.

The release even seemed to please rock fans – an accomplishment rarely achieved by France Gall and certainly never by Sheila! Orchestral direction.

The excellent Jean-Pierre Sabar was responsible for the orchestration of the record – but it’s also worth noting the name of Mike Vickers on the record sleeve. This Brit, born in Southampton in 1940, was known as an influential guitarist, saxophonist and flautist. He played all three instruments in Manfred Mann until quitting in 1965. He cut a solo album – the tragically titled I Wish I Were a Group Again – but it didn’t see the light of day until three years later. By that time, Hardy wanted him on board.

Of course, in the meantime, he had directed the orchestra that, in summer 1967, had backed The Beatles in a live global broadcast of All You Need Is Love. In short, Hardy wasn’t the only one to rate him. Proving that she still recorded in London from time to time, her next release featured Arthur Greenslade. This Kent-born conductor arranged – or would go on to arrange – material for the likes of Serge Gainsbourg, Cat Stevens, Diana Ross, Dusty Springfield and Genesis. He even arranged Goldfinger, perhaps the famous Bond theme of all time, for Shirley Bassey.

For Hardy, on her Vogue EP EPL 866, he appeared on the credits for Où Va La Chance, a cover of There But For Fortune, a song written in 1964 by Phil Ochs and made famous by Joan Baez. Hardy cut a version of the song in English too, but the first version to be issued in France was by Dominique Walter, in 1965.

John Cameron worked with Hardy on Étonnez-Moi, Benoît and La Mer, Les Étoiles et Le Vent. Born in Essex in 1944, Cameron is a composer and arranger who worked with Cilla Black, Donovan and Hot Chocolate.

Above all this, he is known for his instrumental version of Led Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love, which was released under the group name CCS. The song was the theme tune to BBC’s Top of The Pops throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s.

By this time, France was going mad for Véronique Sanson. The singer penned lyrics that were radically different to the kind that people had listened to before. The big female singers of the decade – France Gall, Sylvie Vartan, Sheila and Petula Clark – suddenly all now seemed a little passé in contrast.

Hardy too. Take her Il Vaut Mieux Une Petite Maison Dans La Main Qu’Un Grand Château Dans Les Nuages, the lead track from the Vogue EP number EPL 8652, for example. Written by Jean-Max Rivière and Gérard Bourgeois, this high-quality song failed to appeal to radio programmers.

Only her Gainsbourg-penned releases, L’Anamour and Comment Te Dire Adieu, seemed to fare well. How the latter came to her attention is anyone’s guess. The song had been written in 1954 and popularised by both Vera Lynn and Margaret Whiting – hardly the most obvious material for a hip young singer. With French lyrics courtesy of Gainsbourg, the song went massive.

Géant Vert wrote in Rock & Folk (special issue no. 20): “Issued during the era of the events in the Latin Quarter, music historians have never succeeded in making up their minds about Comment Te Dire Adieu: was it about General de Gaulle or someone less important (Jean-Marie Périer, for example)?”.

Appropriately, Etonnez-Moi, Benoît, written by Patrick Modiano and Hugues de Courson, had something surprising about it. Hugues de Courson is a French musician, composer and producer, and a founder of the group Malicorne. Patrick Modiano is better known as a novelist and, in 2014, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Hardy was delighted when she heard about his Nobel Prize, telling Le Figaro: “His Nobel Prize is amply merited and makes everyone almost as happy as him! I met Patrick Mondiano in the 1960s because of a song he had written the words to and which amused me, Etonnez- Moi, Benoît.

He amused me a lot too – really, his personality was larger than life. He was an acquaintance of Emmanuel Berl, with whom he had made a remarkable and informative book about the last war, Interrogatoire.

Mireille [Berl] asked me to make sure he ate whenever I saw him, which was clearly not happening regularly, given his lack of means and because he was always distracted.”.

In December 1968, Hardy’s latest LP (Vogue CLD-728) was issued. It didn’t include Ouverts Ou Fermés, from her then current 45, but instead offered up La Mésange, a Brazilian tune composed by Chico Buarque and Antonio Carlos Jobim, with French lyrics by Franck Gérald.

Parlez-Moi de Lui featured too. The song is known to English-speaking audiences as The Way of Love, and has been recorded by a variety of artists including Kathy Kirby and Cher. The French original credits composer Jack Diéval and jazz pianist come lyricist Michel Rivgauche, who had written for Edith Piaf, Dalida, Maurice Chevalier, Juliette Greco, Nana Mouskouri and dozens of others.

Of note, too, was La Rue Des Coeurs Perdus, which Richard Anthony had cut in 1959. With French lyrics by Pierre Delanoë, this was a cover of Ricky Nelson’s Lonesome Town.

Hardy also cut the song in English – for her next LP, En Anglais (Vogue CLD-729). Issued at the end of 1969, it was a collection of good songs... but. It is generally thought that the arrangements by top names such as Arthur Greenslade, Charles Blackwell and Jean-Pierre Sabar weren’t as accomplished as they could have been. Were these really the result of fresh recording sessions or had some merely been lingering in a drawer from a couple of years earlier, having been rejected then...?

It was a disparate collection of mostly cover versions: Loving You by Elvis Presley; Let It Be Me, a cover of Gilbert Bécaud’s Je T’Appartiens; Hang On To A Dream by Tim Hardin (and which Johnny Hallyday had cut in 1967 as Je M’Accroche A Mon Rêve); The Garden of Jane Delawnay by underrated British group The Trees; Until It’s Time For You To Go by Buffy Sainte-Marie; Tiny Goddess, which Hardy had previously recorded in French as Je Ne Sais Pas Ce Que Je Veux; That’ll Be The Day by Buddy Holly; Will You Love Me Tomorrow, a 1961 hit for The Shirelles; and Empty Sunday, which had been written by Vicki Wickham and Simon Napier-Bell (and sounded a bit like Christophe’s Marionnettes).

Two other titles should perhaps have featured on the LP: Blue Turns To

Grey, a Rolling Stones track that proved a hit for Cliff Richard, and Oh

Why, originally by Phil Spector trio The Teddy Bears (who are best known

for their 1959 US chart-topper To Know Him Is To Love Him). The song

was also cut in French by Claude Piron and Dalida as Mon Amour

Oublié. (Johnny Hallyday performed it in his live shows too.).

One – Nine – Seven – Zero

Strictly speaking, this album was intended for the English-speaking market. It was released in November 1969 (United Artists UAS 29 046), and heralded the new decade.

Mostly, French listeners already knew – or would soon know – the songs in their own tongue, except the charming All Because Of You, which Hardy re-recorded in German only, as Wie im Kreis. (Interestingly, Jessica Sula cut a version of the song in the 2006 Channel 4 series Skins.).

The album comprised: I Just Want To Be Alone (J’ai Coupé Le Téléphone); Time’s Passing By (Au Fil Des Nuits Et Des Journées); Midnight Blues (L’Heure Bleue); Song Of Winter (Fleur De Lune); In The Sky (Il Voyage); Why Even Try? (A Quoi Ça Sert ?); Magic Horse (Je Fais Des Puzzles); and Soon Is Slipping Away (A Cloche-Pied Sur La Grande Muraille De Chine).

This last song, as well as Les Glaces, would surface on a very rare Brazilian compilation in 1970 (Philips 199 038). The two songs were written by Patrick Modiano and Hugues de Courson.

Similarly, note that The Bells Of Avignon and Soon Is Slipping Away were

issued on a 45 in the UK, although the release was largely ignored.

L’heure bleue...

This four-track release (Vogue EPL 8976), which had Des Bottes Rouges De Russie as the lead song, would be her last EP. After this point, Hardy would issue only albums and singles.

Her next single, J’ai Coupé Le Téléphone (Vogue SP V 45 1655), was

superb. With the excellent Les Doigts Dans La Porte on the flip, it proved

that two good songs were worth more than four fillers. The B-side also

showed that Hardy was very capable of making upbeat songs too, even if

she left the writing of them to other people. Although the style of song

went against her usual one, she agreed to record it to prove that she

could make such a record.

The break-up

Fans were spoiled with a plethora of compilations.

In Germany, a somewhat incoherent compilation was perhaps saved, in part, by a great sleeve. L’Heure Bleue (Philips 6305 007) contained one real gem: Des Yeux D’Enfant. The song built wonderfully and, vocally, it sounded as though Hardy was at breaking point. It was a style that Mylène Farmer would enjoy great success with a decade or so later.

In 1969, against Hardy’s wishes, Vogue published a compilation called International Stars (CLVLX 336). It proved a record that would not rewrite the rules of show business but have profound consequences for the singer. Fans found it interesting for the seven tracks that hadn’t been issued in France before. It also included two older recordings, from 1965, that had appeared on German records, entitled Portrait in Musik, after the famous TV show that she had appeared on. Hardy had refused for the songs to be issued elsewhere, especially in France, as she was unhappy with them.

The two songs in question are classics of French chanson: Les Feuilles Mortes and La Mer. In the English-speaking world, they are perhaps better known as Autumn Leaves and The Sea respectively. The former had been written by Jacques Prévert and Joseph Kosma for the Marcel Carné film Les Portes De La Nuit. It was made famous by Yves Montand, who performed it in the film. Nat King Cole helped make it famous internationally.

As for La Mer, it was written by Charles Trenet and had been performed by many artists, including even Cliff Richard (on his EP Cliff Richard Sings in French, ESRF 1401). The song has a rather sad back-story, having languished half-written in Trenet’s drawer for some time. Then, on 15 June 1944, at about 8pm, as Trenet returned to his home in the Valde- Marne, east of Paris, a car was waiting for him. In it, sat three members of the Gestapo, two of whom got out and insisted on coming into his home. He ran off, heading along the banks of the Marne.

However, he was shot in the leg and collapsed. Fortunately, some neighbours, alarmed by the sound of gunshot, came running, and prevented him from being shot like dog. With a bloody leg, he was driven to a clinic in Neuilly where doctors told him that the nerves in his foot and his sciatic nerve were badly damaged... but that he would be able to walk again after several months of care.

In the weeks that followed, the pain became intolerable, but this was a good sign: it meant the feeling was coming back in his leg. His convalescence proved long and painful – but it gave him the time to write the lines of the song that would define his career: La Mer. He completed the draft in 1946, in the train that took him from Montpellier to Perpignan.