- Françoise Hardy : A Star Is Born

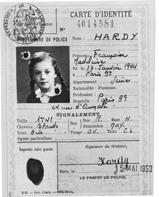

Françoise Hardy was born on the evening of 17 January 1944 in Paris, during an air raid. She is a Capricorn, which, it is said, predisposes her to withdrawal.

Appropriately, then, she remembers herself in childhood as shy and awkward. For her, school playtime was the worst moment of the day, largely because of her frequent falls.

There is little information about her father. He was an ordinary man who headed a flourishing business selling typewriters and calculators – but who was already married. In the 1940s, among the middle classes, people didn’t dare talk about matters of the heart, so the young Hardy was left telling people that her parents were divorced. At the time, in France, this was barely more acceptable than having a single mother, especially at the religious school she went to.

With two or three visits from her father each year, Françoise Hardy can hardly be said to have come under great paternal influence. Her mother, on the other hand, was particularly keen on the education of her offspring: two daughters, born 18 months apart, who didn’t really get on. The younger sister was more playful and sassy, while the elder one led an exemplary middle-class childhood. This model child would play the scales on the piano, then, in her room, listen to the cooings of Tino Rossi, Luis Mariano, André Dassary and her idol, Georges Guétary. She would go and applaud the latter in Pacifico, the operetta he starred in alongside actor and singer Bourvil. She even managed to get his autograph at the stage door – a fleeting taste of the world of celebrity.

Only the most visionary could have predicted a future as an artiste for Hardy – indeed, her next step was to sign up for Greek classes. This avoided those frightening people in the music world. Her dream was more to become an animator or a radio programmer – radio being a medium she discovered only late.

However, destiny proved otherwise. Having passed her baccalaureate with flying colours, she was given a guitar. She would play it incessantly. “I spent many hours of my free time giving birth to melodies or little bits of melodies that borrowed nothing from songs I had heard. In any case, we only had the radio at home very late – in my third year at school – and we didn’t listen to it much.” (Salut Les Copains, February 1965).

However, she also contradicted herself. - "I have to admit that some of my songs were downright excerpts of songs of the time. But in complete innocence” (Paroles et Musique, new series n°9).

She would have been out of step not to do so. At the time, young people were seeking out American and British records, even in Paris. “When I heard something I liked, I would hurry to a record shop on Rue de la Chaussée-d’Antin to ask for it. I went back 20 times to find Neil Sedaka’s Oh Carol.

Still a long way from her mind was the idea of abandoning her studies at the Sorbonne for a career as a singer. She was studying for a degree in German and her language skills would serve her well in later years, when she came to record many of her songs in German.

At this time, the only pop music on French radio came courtesy of an alltoo- short hour on Salut Les Copains on Europe no. 1. Hardy became a keen listener of 208, the French arm of Radio Luxembourg, which, at the time, broadcast pop music every evening.

Her childhood passion for Georges Guétary faded, and she became mad about Cliff Richard, The Shadows and The Everly Brothers. With pop uppermost in her mind, she would compose her very first songs. “My attempts at what I hardly dare to call my ‘compositions’ were made in our kitchen... whose tiling gave an unexpected volume to the sound. A kitchen or a bathroom is a bit like a natural echo chamber. The first song that came out of the kitchen – words and music – was Tu Es Passé Sur La Route. Very quickly, the rhythm of my production reached three or four songs a week... Every Thursday, Mum came with me to the Moka-Cub... where, like many other young composers – interpreters – guitarists, I went with my three songs of the week.” (Salut Les Copains, February 1965) “In Lonely Boy, Paul Anka sang, ‘I’m just a lonely boy, lonely and blue / I’m all alone, with nothing to do.’ I was happy to say the same thing as him in Tous Les Garçons Et Les Filles.”

Her mother, a keen reader of France-Soir, showed Hardy an advert she had seen in it. In four lines, it invited readers to auditions being held by a big record company. Hardy took herself off to Pathé-Marconi, where she was listened to for a quarter of an hour. “I knew I had no chance, but I had to try, to get confirmation of this.” (Platine no. 10).

Just as she expected, the label took her audition no further – they felt she was too similar to Marie-José Neuville, who was known as the College Girl of Song. Hardy was OK about the outcome. “I don’t like my voice, I don’t like what it betrays about my physical limitations.” (Télérama no 2417, 8 May 1996).

This didn’t prevent celebrity photographer Jean-Marie Périer from calling her La Cantatrice – “a nickname that suited her by not suiting her”, wrote Raymond Mouly.

At least Hardy could, for the first time, judge her vocal capabilities for herself by listening to the recording. She suddenly realised that she needed to know how to sing in time. For her, this wasn’t something that happened automatically. Nevertheless, it wasn’t all terrible. “I admit that when I listened to myself, it wasn’t as bad as I had imagined.” (Télerama no 1999, 20 May 1988).

Emboldened by this first, albeit unfruitful, experience, Hardy began a tour of Pathé-Marconi’s competitors. First up was Philips. But there, an audition was out of the question. The label’s policy was to send aspiring stars for singing lessons before its bosses would deign to give them a listen. These classes didn’t come free, and neither Hardy nor her mother had the money for such a luxury, so she passed to the next record company.

Why not Vogue, where, apparently, bosses were looking for a female counterpart to Johnny Hallyday? In the not-too-distant future, Hardy would record an interesting version of Hallyday’s 1963 hit Les Bras En Croix. However, she found his first records awful – so she figured she couldn’t make a worse job of them than him. (She admits today that her own first few recordings were as bad as those of the future king of French rock ‘n’ roll.).

This was in 1961 and the young Hardy had never seen Hallyday live. It wasn’t long before she would change her opinion: “I am very impressed by Johnny when I see him on stage. By contrast, I own very few of his records. On the other hand, I own all the recordings of other artists who, nevertheless, bore me in concert. At the risk of seeming pretentious, I think it’s a shame that some artists tour. They do it because it’s expected of them, but they aren’t really performers.” (Record Collector no. 310) At Vogue, Jacques Wolfsohn, Hallyday’s manager, asked her to interpret two songs from his protégé’s repertoire, Oui Mon Cher and 24,000 Baisers. The results weren’t conclusive and, once again, Hardy was advised to go and take some singing lessons.

So she took two songs – one of which was Je T’Aime Trop, from Elvis Presley’s catalogue (I Gotta Know, in its original version) and signed up with Mireille at the Little Conservatory of Song. She wasn’t the only star to do so. Other students included Pascal Sevran, Yves Duteil, Alice Dona, Alain Souchon, Hugues Aufray and Pierre Palmade.

Her efforts brought fruit: on 14 November 1961, she signed an exclusive contract with Vogue.

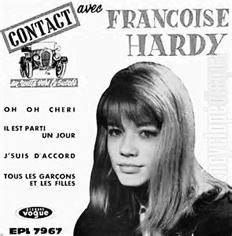

Three months later, Hardy was called in. Wolfsohn, who remembered that she had a similar timbre to her voice as Petula Clark, was looking for someone to record Oh Oh Chéri, which the British star had just turned down. That was only to be expected – the song was already old and hadn’t worked across the Atlantic. Petula had just been voted singer of the year by the readers of Radio-Magazine and was in a position to demand better. Hardy hit the jackpot. She sang several songs and, on 25 April 1962, with four musicians, she recorded four of them. “My first EP was finished in less than a day, in disastrous conditions, with an interchangeable arranger, Roger Samyn, who wasn’t gifted at all, and musicians who were also only slightly.” (Paroles et Musique, New Series, No. 9)/

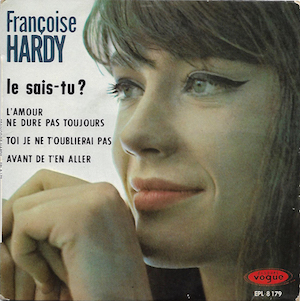

The potential hit, Oh Oh Chéri, was given top billing on the sleeve of the EP when it was issued in June. Another track also charmed several radio programmers, Je Suis D’Accord, J'Suis d’Accord.

As soon as the release began to falter, radio programmers started to play Tous Les Garçons Et Les Filles. Both the words and music had been written by Hardy, even if she didn’t get full credit for them. That was because she hadn’t taken the exam expected by SACEM, the Society of Authors, Composers and Publishers of Music. So she had to share credits with Roger Samyn, the arranger and conductor of the orchestra. It is said that Samyn has enjoyed equal lifetime rights to the song, without having written anything. (Hardy, incidentally, has written most of the lyrics of her songs over the entire course of her career.).

Tous Les Garçons et Les Filles boosted the release further – though Hardy has never been happy with her early recordings. Indeed, when she came to record the song in German, as Peter & Lou, she changed the orchestration. This was in contrast to most artists who cut their songs in a foreign language against the same backing track.

A Special case

In December 1967, she spoke to the monthly Rock & Folk magazine about this first, unforgettable success. “It needed to be recorded differently, with an acoustic guitar and violins and backing vocals – I don’t know – at the end of the day, it should have been recorded properly. Having had such a bad first record, I could hardly have done worse. And yet, that’s what happened!”.

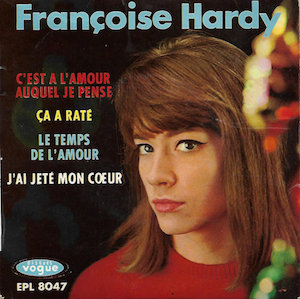

Her view is perhaps debatable. Good songs such as J’ai Jeté Mon Coeur or J’Aurais Voulu needed only a simple accompaniment, which is what they got.

“The young, stick-like, almost androgynous girl, who is both melancholic and mysterious, is something of a special case,” people frequently wrote. Indeed, in 1962, she was at odds with the yé-yé style of the day, as Adamo would be in 1964, and Christophe and Hervé Vilard in 1965 – yet all of them also knew how to seduce adolescent audiences.

It’s not impossible that Hardy’s career could really have come unstuck thanks to an appearance on television. Until that point, opinion had been split, even among the most fervent supporters of the Nouvelle Vague. This is what Salut Les Copains had to say: “People were very divided. ‘She was neither rock, nor twist, she teeters,’ some said. ‘Nothing can prevent her from having something sweet about her,’ said others. As for me, I admit, I was in the negative camp then. I felt that the greatest work of the new generation – that is, the destruction of stuffy songs by a purifying and fanatical rhythm – had been compromised before it had been fully accomplished by a return to paternal romanticism. (Raymond Mouly, Salut Les Copains no. 31, February 1965) - "It took Françoise six long months before she found a fan base among young people”, Mouly continued.

Tous Les Garçons et Les Filles reached number five in the charts in October 1962. Hardy’s global conquest would happen a few weeks later. The announcement in autumn 1962 of the results of a referendum on the direct election of France’s president was sure to attract plenty of television coverage. There was, after all, just one TV channel. Between two sets of results, viewers had to watch Mademoiselle Hardy. She came across well to children and parents alike, so, subsequently, the latter could hardly refuse their children’s requests for the pocket money needed to buy her latest 7”. (At the time, an EP – the most common form of 7” – was priced at 9.90 francs, equivalent to €1.50.).

This is, arguably, the most likely explanation for the success of Tous Les Garçons Et Les Filles. At over three minutes long, it was too long for radio, and the song seems too simple – Hardy never stopped saying that she only knew three chords on the guitar. As for the lyrics, apart from borrowing from Paul Anka’s Lonely Boy, they were inspired directly by Hardy’s own personal experience.

Sales proved strong. By the end of 1963, she had sold some two million records. Indeed, as Édith Piaf lay dying, some commentators rather tactlessly remarked that Hardy had sold more records in 18 months than Paris ‘Little Sparrow’ had in 18 years.

Wearing her heart on her sleeve

Songwriters often search their souls to be able to come up with material – Hardy, more than most, some would say. - "You can really feel that her songs reflect her own feelings. She knew how to translate in a pleasant way, the first phase of the life of a young girl, of finding love” (Edgar Morin, sociologist).

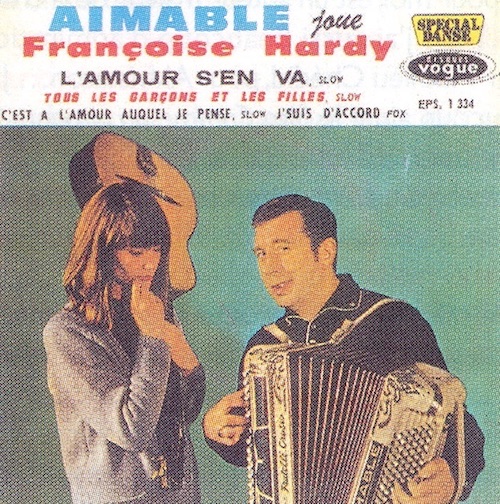

Throughout her albums, we would see the highs and lows of her love life stamped on her songs. As Waltersmoke wrote, quite justly, on the website Nightfall Forces Parallèles, when describing her second album: “Sadness clearly becomes the very foundation of Françoise Hardy’s success. You need only to read the titles of album’s songs and all is said. This is notably due to the singer’s preference for love on the skids, that doesn’t go smoothly, or that doesn’t end well. In addition, the love themes are always written poetically, even on cover versions or other songs. Except for Le Premier Bonheur du Jour (The First Happiness of the Day), it is easy to cite L’Amour Ne Dure Pas Toujours (Love Doesn’t Last Forever), with its pertinent jazzy organ, as an example, to show realistic pessimism”.

What was true in 1963 was also true in 1962. She felt loneliness intimately, and had the impression that no one was attracted to her. Nevertheless, the hits followed at a rapid rate. The next was nothing more than a reworking of an instrumental by Les Fantômes called Fort Chabrol (Chabrol Fort). Giving it words transformed it into Le Temps de L’Amour (The Time of Love). It also gave Hardy the chance to meet Jacques Dutronc, who wrote the song and would go on to father a child, Thomas, with her.

Originally, Fort Chabrol stood little chance of becoming a hit. Its title – an episode during the Dreyfus affair in 1899 when the government feared a royalist riot – did not speak to the youth of the 1960s. The title Le Temps des Copains (The Time of Friends) was suggested, but it had just been used for a television show. So, in the end, it became Le Temps de L’Amour. However, Dutronc didn’t write the lyrics for his future wife. In fact, the song had appeared on the debut record by José Salcy (EP Vogue EPL 7966) before being reworked by Hardy in both French and Italian (the latter became L’Età Dell Amore).

The Dutronc-Hardy couple wasn’t exactly predestined, as Hardy explained in Salut Les Copains n°62: - “I was looking for a guitarist to come on tour and my artistic director said to me, ‘I know a guy who could do it. He’s a good guitarist, he’s just back from military service and he’s very funny. He’s called Dutronc.’ The same day... I bumped into him. Delighted by this coincidence, I explained my little problem to him. He looked at me oddly and replied evasively to my offer to work: clearly, he didn’t care. So I took on another guitarist, Bernard Ferrau.” The same Salut Les Copains article also revealed that Dutronc was engaged to a nice girl from a good family at the time. It would "cause a scandal if he started to adopt a bohemian lifestyle”, the piece said, while noting that his fiancée hated music.

Over the years, without ever really entering the charts, Le Temps de L’Amour has become a classic. Dutronc himself even included it in his repertoire during the 1980s. In the words of the song itself, "The time of love, is long and is short, it lasts forever…”.

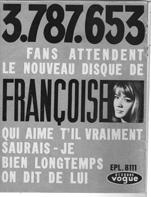

3,787,653 fans await her new record

The exact number might be an exaggeration, but Hardy remained hugely popular among the French for the remainder of the decade. And, in 1965, Billboard magazine upped that number by a factor of 15: “46,500,000 Frenchmen can’t be wrong,” it proclaimed. “Françoise Hardy is the greatest!”.

As a recording artist, Hardy was a star. What she needed was to consolidate her position by going on tour. Over several months, she played regional venues as part of the Gala Des Étoiles (Star Gala). She wasn’t the headline artist, but as each evening went by, she won over more and more young people.

She also performed for prison audiences, notably at Fresnes, France’s second-largest prison, located south of Paris. A young guitarist by the name of Django Reinhart – known as Babik – was serving time there, and Hardy would meet him again around 40 years later.

At the end of this exhausting exercise, on 7 November 1963, Hardy appeared at the prestigious Olympia venue, as the warm-up for Richard Anthony. There, she would face an audience that was partly indifferent, partly hostile. Of the 2,500 seats, 1,000 were given over to Parisian show business people, their artists and journalists – “the weather forecasters of song”, as Salut des Copains editor Raymond Mouly called them. It’s well known that comped audiences clap less fervently. However, the other 1,500 people, who had paid for their tickets, were delighted with her performance.

They were keen to let others know too – as the annual poll run by monthly magazine Salut Les Copains demonstrated. In 1964, the arrival of France Gall on the scene saw Hardy slip back to fourth position, from third a year earlier. She regained her place in 1965, and remained in the top three for the following three years. In 1969, she dropped a place again, this time in favour of Mireille Mathieu.

Time for an LP

Her first three EPs could have been stamped Made in France – they were French compositions with lyrics by Hardy, except in the case of Oh Oh Chéri, which Jil and Jan (Gilbert Guenet and Jean Setti) had written the words for. The pair were already well established as writers for Johnny Hallyday.

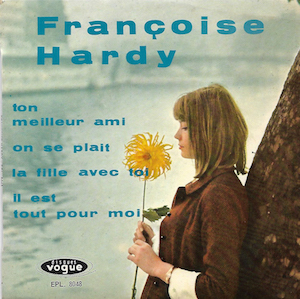

The third EP, Ton Meilleur Ami, came in a particularly romantic-looking picture sleeve.

The impending arrival of Christmas meant the time had come for Hardy’s first album. In time-honoured tradition, this would compile the songs of her first three EPs – and be a sure-fire stocking filler.

The cover photo was taken by Jean-Marie Périer, Hardy’s then boyfriend and a photographer with the monthly Salut les Copains magazine. Périer was understood at the time to be the son of actor François Périer, though it would later emerge that Henri Salvador was in fact his father. (That both he and Hardy grew up without father figures may perhaps explain their close relationship.).

With 12 familiar songs, the album offered little by way of surprise. In fact the most surprising thing about it was its cataloguing: it was given the reference LD 600-30. This would confuse collectors over the years, as her second album would carry the reference FH1 – that is, the singer’s initials plus the number 1. This made no sense for a second album and the confusion would last for years.

1963 : inspired choices

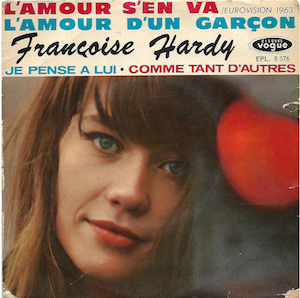

Embarrassingly, Hardy’s record company displayed a touch too much optimism over her first release of 1963. She was lined up to represent Monaco at that year’s Eurovision song contest with the song L’Amour S’En Va. The first pressing of the EP carrying her entry declared on both the front and back covers and on the label itself that it had won the pan- European popfest. Ahem, this was even before the contest had been held – and it proved rather awkward when the song finished a lowly fifth. Needless to say, the cover was later changed.

Unusually, two of the songs from the EP, and two from the follow-up, wouldn’t figure on the singer’s next album. This wasn’t because they were particularly poor – quite the opposite. However, it meant that fans who hadn’t bought the EPs would have to wait years to lay their hands on Je Pense à Lui, L’Amour S’en Va, Bien Longtemps and Qui Aime-t-il Vraiment.

This second album is a marvel. OK, it doesn’t contain any hits the size of Tous Les Garçons Et Les Filles, but all the tracks were of a high quality. The strong yet delicate J’aurais Voulu proved one of its highlights. She also cut the song in Italian, as Vorrei Essere Lei, and brilliantly in English as I Wish It Were Me, with a much richer orchestration. The piano arrangement and the more pronounced violins made this altogether different to the French version.

The first couple of tracks on the album – Le Premier Bonheur du Jour and Va Pas Prendre un Tambour, composed by Jacques Dutronc – could often be heard on the radio.

The second album called time on Hardy’s 100% French recordings. From the next release onwards – an English-language release – the singer would benefit from the vast talent of British musicians and arrangers.

The big screen

In 1963, director Roger Vadim had her debut on the big screen in Château en Suède (released as Nutty, Naughty Chateau, in Englishspeaking territories). The film was an adaptation of the theatre piece by Françoise Sagan, and Monica Vitti headed up a dazzling cast ("I had a lot of trouble with it, particularly with the drunken scene: I had never drunk in my life… Vadim made me drink vodka to liven me up a bit”).

Hardy took the role she was offered but then turned down a part in Cherchez L’Idole, a pop caper starring many big names of the day, including Sylvie Vartan: "I’d read the premise of the film. It was worse than Tintin and Milou!” Hardy said. "And also, I didn’t want to sing in a film – and as I had just finished Château en Suède, I preferred to wait for a worthwhile role”.

She made a sweet appearance right at the end of the film What’s New Pussycat ?, which was shown in Parisian cinemas between October 1964 and January 1965. This gave Hardy the chance to cross paths with a young actor and playwright by the name of Woody Allen. In fact, although the film was American, French actors such as Capucine, Annette Poivre, Jacques Balutin and Jean Parédès starred alongside big international names including Peter Sellers, Peter O’Toole and Ursula Andress.

In mid-1965, in Greece, Hardy appeared in Une Balle au Coeur with Sami Frey. Known as Devil at my Heels to English-speaking audiences, the film told the story of a man who has been cheated out of his castle. He tries to avenge himself and get back his home, but things don’t go quite to plan.

A year later, in 1966, Hardy took a role in Jean-Luc Godard’s Masculin Féminin, alongside Jean-Pierre Léaud, Chantal Goya and Marlène Jobert.

That same year, she found herself in Italy, on the circuit at Monza, where, with Yves Montand, she appeared in the film Grand Prix. As its name suggests, this John Frankenheimer production was set on the race track. Indeed, over five months of filming, Hardy visited all the Formula 1 circuits. Racing car champion Jean-Pierre Beltoise was on hand to make sure that the stars weren’t put at the slightest risk in any of the scenes. On 21 December 1966, Hardy was invited to the premiere of the film in New York. This short trip to the US encouraged her record company to publish her material there.

Her adventures in front of the camera were almost over. In fact, it would be another ten years before she would be seen on the big screen again – this time, with Catherine Deneuve in the film Si C’était à Refaire, directed by Claude Lelouch.

This wasn’t the first time Hardy had met Lelouch. Back in 1963, she had recorded a Scopitone – these films were a sort of forerunner to music videos – under the direction of this then newcomer. It was filmed on the main drag of the Foire du Trône festival in Paris and Hardy didn’t recall the experience with fondness. "I don’t have a good memory of it”, she told the monthtly Platine magazine (n°10) "because very quickly I had the feeling that Lelouch was making fun of me”.