- Françoise Hardy : Soaring High

Given Hardy’s talent as a songwriter, it’s easy to forget that, like most of the yé-yé girls of the 1960s, she also hunted for international hits to cover. In the early 1960s, she sought out British and American songs, before moving onto Italian material in the middle of the decade.

Indeed, it was precisely this international sound that interested bosses at the Vogue label – not songs such as Tous Les Garçons Et Les Filles. No one at the record company really believed in that track, not even after it was released. “She sang with conviction, application and awkwardness,” wrote Eric Vincent in Salut Les Copains no. 137.

Instead, Vogue bosses were more attracted by the prospect of having her record a French version of Uh Oh, a song in 1958 written by little-known American rockabilly Bobby Lee Trammel.

In 1967, Hardy described the situation she found herself in during the early years of her career: “When you are starting out, you are a bit obliged to make concessions and to record some tacky titles here and there so as not to upset anyone. In my case, I didn’t have to fight with anyone because I composed almost all of my songs. When I recorded a cover version, it wasn’t intentional – it was the result of a competition of circumstances… In fact, I would like to do fewer and fewer cover versions.” (Salut Les Copains no. 60).

In 1962, Hardy wrote French lyrics to Barbara Lynn’s You’re Gonna Need Me, transforming it into Je Te Manquerai. This R‘n’B-styled number would be just the sort of track that she would cover well – though, sadly, nobody ever got to hear it, as she opted not to record it.

For some songs she covered, the choice seemed much more obvious. Paul Anka was Hardy’s idol, so his Think About It – which became Avant De T’En Aller for her – was almost a given. L’Amour D’Un Garçon, a take on The Love Of A Boy, by Timi Yuro and Julie Rodgers, and even Qui Aime-T-Il Vraiment (Your Nose Is Gonna Grow, by Johnny Crawford) were other obvious picks. They were very much in the romantic style Hardy was known for.

Perhaps the most surprising choice was that of A Wonderful Dream by The Majors, which became Je Pense A Lui. The issue wasn’t that it was a poor song – quite the opposite – but it was far removed from Hardy’s usual style.

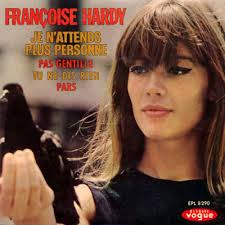

Connie Francis’ It’s Gonna Take Me Some Time became On Dit De Lui for the French star, and no one could find fault in how she adapted her style to this number. The tall, shy girl proved she knew how to be sexy. British rocker Marty Wilde’s tuneful top ten hit Bad Boy became Pas Gentille for the singer, while the inappropriately named The Joys’ decidedly mediocre I Still Love Him still failed to evoke much pleasure for Hardy fans as Pourtant Tu M’Aimes.

There’s a definite Hardy style that comes through clearly, both on original songs and on cover versions. Try it out on Quel Mal Y-A-T’Il A Ça, her take on Patsy Cline’s When I Get Through With You. Now listen to C’Est La Première Fois, Hardy’s version of Your Tender Look, a hit for Britain’s Joe Brown. Hardy’s style is decidedly all her own.

She failed to cash in on some big British hits that would have suited her well, however. She left Richard Anthony to nab Dusty Springfield’s debut solo A-side, I Only Want To Be With You (A Present Tu Peux T’en Aller), opting instead for the inferior flip, Once Upon A Time, which became C’Est Le Passé.

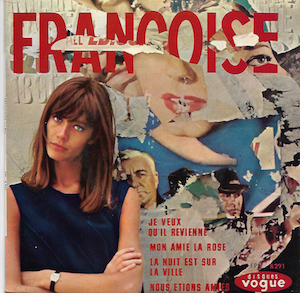

It’s possible that Hardy hooked up with top British arranger and composer Charles Blackwell to avoid putting up with competition from her Parisian counterparts for material. That way, she had fresh material all to herself – and could even enjoy the luxury of recording the same song in both France and English. Je Veux Qu’Il Revienne is a case in point. She also recorded the song as Only You Can Do It at around the same time as the Vernons Girls cut it.

“It was a blessed, easy period for me,” Hardy has since said. “While in France, musicians accompanied so-called yé-yé singers so they could put food on the table and received contempt for doing so. Over in London, they played well and were at least discreet enough not to let it be known what they thought.”

Hendrix takes charge

From her fourth release – the self-penned L’Amour S’En Va – onwards, Hardy’s sound came into its own. Exit Roger Samyn, whose orchestra had accompanied her on her first album. Enter instead Marcel Hendrix for her second LP – and a discernibly richer sound.

This sound can be enjoyed on Hardy’s subsequent EPs, whose titles were all taken from the FH1 album.

The English-language four-track EP, En Anglais, issued in 1964, was completely new, however. Alongside three adaptations of her own material was Catch a Falling Star, an update of a 1958 hit for Perry Como.

All Over The World made number 16 in June 1965 and had been written in a hotel room in Brazil while Hardy pined for Jean-Marie Périer (“I spent my time crying in my room during tours,” she said). Their relationship would last from 1962 to 1966, but each had a successful career and this would, ultimately, keep them apart.

The sleeve of All Over The World noted that Hardy had been accompanied by the orchestras of Bob Leaper and, in particular, Tony Hatch. The latter was known for his work with Petula Clark, as well as with many other top stars of the day, including The Searchers, The Overlanders, The Breakaways, Julie Grant and even a certain Sacha Distel.

Tony Hatch was more than just an arranger and orchestra leader – he was also a pianist and a composer. In 1964, he met singer-songwriter Jackie Trent, and the pair married two years later. They also penned many songs together, including plenty of international hits for Petula Clark.

It’s fair to say that during her time with Tony Hatch, Hardy was in good hands.

For her next release, however, Hardy opted to call upon the talents of Mickey Baker, half of the duo Mickey and Sylvia, who had scored in the US in 1956 with Love Is Strange. (The song enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1980s when it was included in the soundtrack to Dirty Dancing.) The release, another four-track EP, led with Pourtant Tu M’Aimes. None of the tracks really stood out and three of them would even be left off Hardy’s third album, the illogically numbered FH2.

She stuck with Baker for her follow-up EP, though she would re-record one of its tracks, Et même, back under the watchful eye of Charles Blackwell.

Charles Blackwell

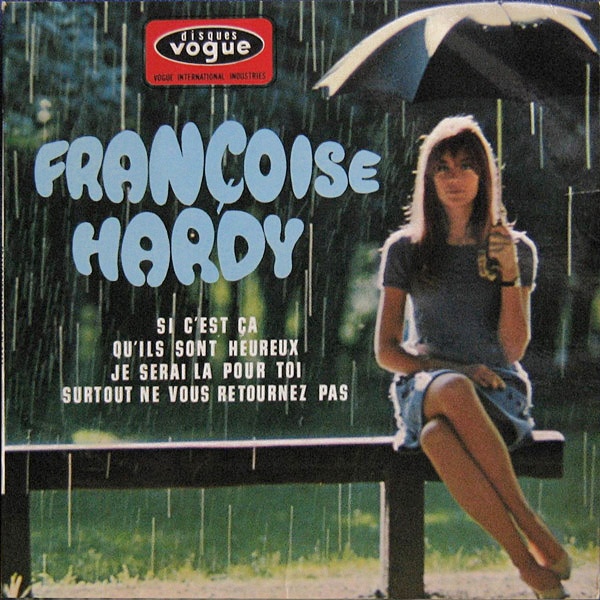

If Hardy had always been a bit ashamed of her early recordings, she had no reason to be embarrassed by those with Charles Blackwell. Cut in both London and Paris, these recordings were simply first-rate. Not only that, but the sessions also enabled Hardy to work with core Led Zeppelin musicians: Jimmy Page on several titles and John Paul Jones on a couple of tracks (1967’s En Vous Aimant Bien and Mais Il Y A Des Soirs). During this period, Johnny Harris stepped in to provide the orchestra for one session. Completely unknown in France, this Scot arranged several of Hardy’s best songs in 1966, including Comme and Si C’est Ça. On them, Hardy sounded on the very verge of tears, bringing a romanticism that was sometimes missing from Blackwell’s work.

Hardy’s dealings with Blackwell had begun in 1964 with Je N’Attends Plus Personne, a cover of Italian star Little Tony’s Non Aspetto Nessuno. The follow-up proved even better. It included three hits: Je Veux Qu’Il Revienne, Mon Amie La Rose and La Nuit Est Sur La Ville. (The fourth track was the weak link of the selection, Nous Etions Amies, a faithful cover of an ultimately forgettable Italian song, Eravamo Amici.).

Hardy’s collaboration with Blackwell lasted officially until 1968 with Now You Want To Be Loved / Tell Me You’re Mine (though the songs were actually recorded the previous year).

She recognised his input in an interview in 2005 with monthly magazine Record Collector (issue 310): “I really think my records are only good from the point when Charles Blackwell started working with me in 1964.” Did they part on bad terms? Well, certainly Hardy was never satisfied with his orchestration of Il N’Y A Pas D’Amour Heureux. The version found on the album CLD 728 was remade with Jean-Pierre Sabar. Plus, Quand Tu Viendras was recorded in 1964 but not released.

1965

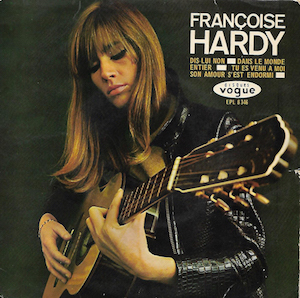

1965 started well. Dis Lui Non, a cover of Bobby Skel’s Say It Now, was a hit. On the same EP was Dans Le Monde Entier – a big hit in Britain as All Over The World – and Son Amour S’Est Endormi, a take on German singer Tommy Kent’s 1960 hit Alle Nächte. (The fourth track, Tu Es Venu A Moi, was the weakest.).

There was no let-up in quality with Le Temps Des Souvenirs, a track cowritten by Charles Blackwell and recorded at the same time by PJ Proby as Just Call And I’ll Be There. However, J’Ai Bien Du Chagrin – a hymn to alcohol – and the EP’s two other tracks, Tu Ne M’Attendras Pas and Bout De Lune, were little more than filler.

The follow-up was distinctly better, with Ce Petit Coeur, En T’Attendant and L’Amitié. The latter had been written by Gérard Bourgeois and Jean- Max Rivière, two guys who had written most of Brigitte Bardot’s hits – or certainly more than Serge Gainsbourg had! The fourth track was Non, Ce N’Est Pas Un Rêve, which Blackwell had co-written and which was also recorded in English in a more dramatic style by Samantha Jones, as Don’t Come Any Closer.

That year, Claude François would once again cut the ballad of the summer season. The release of his Quand Un Bateau Passe, a take on the Burt Bacharach’s Trains And Boats And Planes, would pip Hardy’s version to the post and hers remained unreleased.

1966

In 1966, Hardy enjoyed two massive hits with songs that were versions of Italian songs. The first, Je Changerais D’Avis, was a take on Mina’s Se Telefonando, while the second, La Maison Où J’ai Grandi, was a cover of Adriano Celentano’s Il Ragazzo Della Via Gluck. Of the latter, Hardy said: “I had heard it at San Remo, I found it terrific but I never thought for a minute that it would be available for adaptation in France. And when I brought it back, my artistic director didn’t want me to record it. I did it against his wishes.” (Salut Les Copains, no. 60).

It was also from Italy that Hardy brought back Il Est Des Choses – or Ci Sono Cose Più Grandi. The EP also included the excellent Guy Bontempelli composition Tu Verras and the Hardy original Je Ne Suis Là Pour Personne, on which Blackwell recreated a Shadows sound by way of introduction. Blackwell recalls: “I had to go to Paris to hear the songs but the recordings were made in London, at Pye’s studios. She chose the songs herself, keeping control. We never worked on them together from draft stage onwards – no, she preferred to listen to the English versions that I suggested for her and, then, she would add her own lyrics. She knew how to cool and heat up the atmosphere: she groaned and breathed deeply to get herself in the right place.”.

Hardy agreed, though not in quite the same terms. “Sometimes I know what I want to hear and I am incapable of explaining it.” (Notes, La Revue De La SACEM, no. 153) “Singing isn’t natural to me and sometimes obliges me to prepare myself by sorts of strange means – by hitting the baton, for example – or by grimacing to emit certain notes that are too high or too low.” (Le Désespoir Des Singes… Et Autres Bagatelles).

Blackwell didn't only lavish praise on Hardy, however. “After two of three takes, all was good, but she insisted on doing around 20 takes of every song. Personally, I never heard the difference; she was a perfectionist. Mick Jagger and his entourage often came to help at sessions.”

FH3

1965’s FH3 was another ideal Christmas present of an album – perhaps even more so than its predecessors. For the first time, it contained material that hadn’t already been released, notably the excellent Je Pensais and Tout Ce Qu’On Dit.

The year had gone well and Hardy was able to grant herself a wellearned holiday in Switzerland before appearing at Paris’ prestigious Olympia venue as part of Disco Parade. However, this life in the fast lane was beginning to take its toll on her. She saw her boyfriend, Jean-Marie Périer, rarely – and briefly.

The public, of course, only saw the artist, not the private person who often suffered from loneliness. Although 1966 and 1967 were as successful for her as the previous years, she paid the price. “This tear on my cheek, it is nothing but a little rain,” she sang on Rendez-Vous D’Automne, one of her hits of 1966.

During the time, Tous Les Garçons Et Les Filles – a song composed out of need, without hurt and quite spontaneously – became the hymn of a generation. Even the Rolling Stones saw in it a source of inspiration for their 1965 global hit (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.

For many Britons and Americans, Hardy represented the ideal French woman. This put her in the same class as Brigitte Bardot – despite their physical differences. Hardy became known as ‘the yé-yé girl from Paris’.

Her notoriety had crossed the Atlantic, with numerous articles appearing in the American press. Bob Dylan for one was taken by her. Having succumbed to her charms, he dedicated a poem to her on the reverse of his album Another Side of Bob Dylan (see below). When he came to put on a show at the Paris Olympia in May 1966, he refused to sing until she came and saw him in his dressing room.

Having become an icon in Britain, she re-recorded some of her best songs in English, as well as some songs she hadn’t issued in France. Her British releases dated back to 1964 and proved successful.

There are at least 50 songs that Hardy has sung in English – including remakes of her own hits (such as Mon Amie La Rose, Rendez-Vous D’Automne and Dis-Lui Non). Others were takes on songs by other singers, and we’ll look at these in depth in the next chapter.

Some records of the same period :